Now Reviewing at Game Chronicles

April 18, 2011

It seems I’ve been a little lax with the blog. I’ll try to keep the updates coming a little more often. I’ve been doing game reviews for Game Chronicles. I figure it’s worth the writing practice, and having to articulate what I think about a particular game helps me think about it more critically. So far, I’ve got a review of Tales from Space: About A Blob, with more on the way.

Some Graphic Design Work in Tengwar

March 4, 2010

I may be done with school, but I’m still doing graphic design work to keep myself on my toes and keep myself from getting too rusty on the tools I use. Here’s a couple exercises I took on.

This is the Youtube logo rendered in Tengwar, the lettering system that JRR Tolkien created for Middle-earth. I redrew every single letter in Illustrator. I feel like some of the strokes could be a little smoother, but as a whole, I’m proud of this. I don’t like to leave a job half-done, so I spent even more time actually making sure that everything was correct. I ended up learning an awful lot about how the Elvish script works. Did you know Tengwar’s written phonetically and there’s actually two different Elvish languages? I sure didn’t. I think it’s kinda interesting that vowels are actually placed above or below letters, too.

Here’s the Viddler logo. Because it’s a more obscure video site, I’ve included the original logo. The gradient effect isn’t exact, but I learned a lot making it. Figuring out an angle for where the text cuts into the camera took a lot of tries, but I’m satisfied with the result.

The Navigation of Deadly Premonition

March 1, 2010

I recently bought a copy of Deadly Premonition on the Xbox 360. After seeing video of it, it seemed like a quirky game I might appreciate, and for $20, I wouldn’t mind giving it a chance. After having played it for a few days, I think it’s definitely an interesting game that people should try out. I wouldn’t say it’s an excellent game, but it’s a unique hybrid of a Shenmue-style sandbox world and a Silent Hill survivor horror game that I most definitely enjoy.

I’d like to say again that I enjoy playing this game. Deadly Premonition is definitely a quirky piece of work. The main character, an FBI Agent nicknamed York, is pretty clearly a lunatic, and the other people in the town you explore are visibly uncomfortable dealing with him. The game is loaded with atmosphere, and the small town is filled with things to do. When you aren’t working on the case, you can explore places to look for Agent Honor badges, talk to the townspeople, buy a new car, perform part-time work to help out the inhabitants of the town, and many other things. I can’t emphasize enough that I found the game enjoyable, in spite of the issues that plague the game.

However, it does have its issues. The first thing anyone mentions is that the graphics aren’t pretty. They aren’t. Enough said there, moving on. The biggest issue I have with the game is the user interface. More specifically, the map. In regards to moving around the town, the user is given all the information they need to get from place to place, except maybe an icon to indicate the location of a car they can drive. This usually isn’t an issue, because your car is usually going to be where you left it, and is usually within spitting distance. However, the way the information in the map is presented to a player generates a lot of confusion.

I’d like to go over this step by step. There are three distinct map methods. The first is a circular mini-map that shows the immediate area during normal play. It shows maybe two blocks around York, who is represented by an arrow pointed at the top of the screen. There is also a compass indicating which way is north. This map is fine. I have no issue with it, though a method to make it zoom out a little would have been nice. Symbols indicating points of interest are displayed as well.

The second map is accessed by pausing the game then highlighting the Map option, but leaving it there without selecting it. This map covers the entire town and cannot be manipulated in any way, not even zooming in or out. The scale is small, but you can make out bodies of water, roads, and railroad tracks. However, there is no icon to indicate York’s present location or any points of interest, and the entire thing is brown. It seems intended to serve more as an very large symbol of a map, but because of the third map, it’s forced to function as more than is intended.

The third map is accessed by actually selecting the Map option. This brings up an area of maybe 4-5 blocks around York. Like the circular map overlay displayed during normal play, this is in full color and has icons indicating points of interest and an arrow representing York’s current location and facing. Unfortunately, the compass indicating which direction is north does not always point up. The arrow indicating York’s facing, on the other hand, does. The area of 4-5 blocks is also the maximum zoom on this map, though the area of the map shown can be moved with the left analog stick.

These cause serious UI issues. A player has extreme tunnel vision and in almost all cases, cannot see both their current location and the location they would like to visit on the map at the same time. These are the steps I had to end up using to go from one place to another.

Step 1: Make sure York is facing north.

Step 2: Call up the map and memorize what the area around York looks like.

Step 2: Use the shoulder triggers to switch the focus the map through every single point of interest until I find the location I’m looking for. Alternatively, use the left analog stick and slowly scroll around the very large map until I happen to, by blind luck, come across the place I want to visit.

Step 3: Memorize what this area looks like.

Step 4: Back out of the map screen and into the pause menu screen.

Step 5: Look at the large zoomed out map that shows the entire town, which has no icons indicating anything. Try to find out where York is and where I want to go, trying to remember what each of the places looked like.

Step 6 (Optional): Realize I forgot what a place looked like. Repeat steps 2-5.

Step 7 (Optional): Realize that York wasn’t facing north, so the actual scrollable map is a rotated version of the large town map, so those memorized locations aren’t going to be anywhere near as useful. Exit all menus, face north, and repeat steps 2-5.

Step 8: Figure out a route and go there. If I forget where to turn, then I need to either face the car north or exit the car and face north, then repeat steps 2-5.

I enjoy this game. I really do. But the lack of attention to the user interface here should have been picked up in quality assurance at the absolute latest. Getting from place to place in a game where its most prominent feature is a town with a lot of things to do shouldn’t be this difficult a task.

Help Haiti, get $1,500 in RPG Product

January 22, 2010

The list is over here

There’s some GOOD STUFF here. Spycraft and Trail of Cthulhu, even.

On top of that, they match donations.

Escape from Midnight Mansion Final Prototype Photos

September 23, 2009

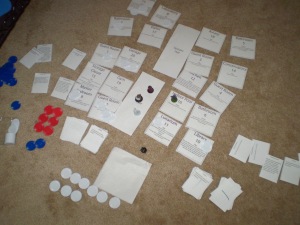

This board was quite a bit of work. Every graphic on the board was designed by me. The game requires that a room be randomly selected by rolling a 20-sided die, so I made the numbers stand out as much as I could to make them easier to find, while still being lower on the page hierarchy. Information that players need quickly, such as legal moves, the clock, and the turn order, have been placed on the large central portion of the board. Because of the game’s Halloween Horror feel (a term I used in the early stages of concept work, referring to a sort of kid-friendly tongue in cheek scary-yet-funny mood), I wanted to stick with black and white as strong colors, with black featuring predominantly. After some internal debate, I allowed myself to use a third color, red, when an element of the board needs to stand out. In this case, the legal movement through the game. The black and white version did not stand out well against the drawn room borders.

The individual tiles are made of cardstock mounted on foam core board. Unlike the paper prototype, they’re much easier to lift up off the playing surface, since they’re nice and thick. I was originally hoping to find a place that could put them on chipboard or whatever most board games are mounted on. Altogether, the whole assembled board is 20 inches by 20 inches, about the size of games such as Monopoly and Clue.

I plan on having this sold at a certain site soon, but the board cost may be prohibitively expensive. The game mechanics are fine as they are, though they might need a little tweaking, but the price of all the tiles is unacceptable. I plan on redoing the graphic design and potentially messing with the layout so that each room will fit on a playing card, which will be considerably cheaper to produce. Sometime in the future, it might be nice to be able to sell it at its full size, though.

Escape from Midnight Mansion: Initial Prototype Playtest Photos

September 19, 2009

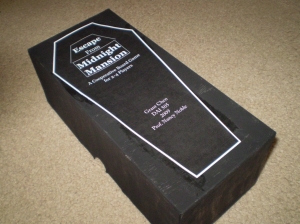

Escape from Midnight Mansion: The Unboxing

September 15, 2009

Current Projects

September 13, 2009

As much as I love video games, I’ve been thinking a lot about “traditional” games lately. Board games, tabletop role-playing games, card games, miniatures war games, that sort of thing. Part of it is that as a designer, I want my products to go through as much iteration as possible and I want the ability to make changes myself so I don’t have to wait for a programmer to do it for me before I can resume work. Traditional games are pretty good at this. They’re also very affordable to prototype.

I’m working on a number of projects, not counting the current proofreading for Tenra Bansho Zero. The first is a series of Dungeons & Dragons 4th edtion supplements. I’m working on this with a friend right now. I won’t say too much about it, but I think it’s safe to say that it addresses a cultural niche that we think needs to be filled. Another project is the retooling of Escape from Midnight Mansion to make it suitable for sale with the resources currently available to me. I also have a very silly card game in mind, which I’d like to publish before EfMM. It’ll be cheaper and it’ll give me a better idea of what to expect once I toss the product out there.

The last of the projects I’d like to mention for now is a complete tabletop roleplaying game system. This one’s been occupying my attention a lot lately. I’m in the early stages of development. I’m going to have to say that having to do research on TVtropes is much more difficult than I thought it would be. In terms of systems, I’m looking at different die sizes and combinations and how they weight the distribution of results. I might be getting a little ahead of myself, but there’s a probability curve in my head that I’ve become curious about. I’d like to see how that affects the game. More on that later.

Escape from Midnight Mansion

September 10, 2009

Over the past several months, I’ve created a cooperative board game for children between the ages of 7 and 10, titled Escape from Midnight Mansion. I hope to sell it soon. There are a few sites I have in mind where it could be sold. The Game Crafter is a site where I could upload pdfs and select game components, and I can sell my game to people through that site. The current design will have to be reworked for cost reasons, though.

The current design of the game involves a series of 22 small boards, and unfortunately, every board in a game at The Game Crafter adds two dollars to the price of the game. It’d be prohibitively expensive. One solution in mind right now is redesigning the boards so they become cards instead, which are much cheaper.

I’ll explain how the game works once I can figure out how much I can openly talk about it, but it’s got some ideas I’m pretty proud of. My inspirations include Pandemic, Shadows over Camelot, Betrayal at House on the Hill, and Arkham Horror.

Shadows Over Camelot

July 7, 2009

Yesterday, I had the chance to play one of the games I considered as possible influences for my own cooperative board game concept, Shadows Over Camelot. In this game, the players take on the roles of the Knights of the Round Table, and together, they try to defeat the board itself. By default, there is a chance that one player may secretly be a traitor (though this is not guaranteed) trying to make sure everyone else loses, but that option was not exercised because we were still trying to learn how the game is played.

Each player’s turn consists of two parts. In the first part, titled Progression of Evil, the players must choose one of three bad things to happen. They can draw from a black deck of cards, which causes a random bad event to happen. They can choose to sacrifice one of their points of life. If they run out of these, they are eliminated from the game, though there is a way to save them. The last is to place one siege engine on the board. I’ll address the siege engines later.

In the second part of a player’s turn, and this is a very simple explanation of the mechanics, the players can take on a quest, perform an action related to a quest, try to restore their life points, or destroy a siege engine. If a quest is successfully completed, the players can restore their health and place white swords on the Round Table in Camelot, and sometimes other effects occur.. Black cards that are drawn create complications for quests, whether the players are there or not. If a quest is ignored for too long, the quest may be lost, anyone on the quest loses a life point, and black swords are placed upon the Round Table in addition to other possible effects. When there are at least sixteen swords on the Round Table, the game ends.

There are three loss conditions in the game and a single win condition. If all of the knights lose all of their life points, the forces of evil win. If the game ends with 6 or more black swords on the table, the forces of evil win. If twelve siege engines are placed on the board, the forces of evil win. If the game ends and none of these three events occur, then the forces of good win.

As a cooperative game, several elements stand out. The presence of a traitor aside, victory and defeat are both shared. Players are not in competition with each other for victory, a vital, if obvious, observation. Another is that the game still has conflict, as it well should. A game without conflict or some sort of challenge to overcome would be boring, and player actions would have no meaning. In most board games, the conflict comes from other players, but here the conflict comes from the game itself. Unless there is a traitor, or someone falsely suspects someone else of being a traitor, players acting rationally will not try to oppose or otherwise hinder each other. The players must cooperate to beat the game, and here lies the challenge and meaning of the game.

Effective play of Shadows over Camelot requires the players to not simply work together, but to work together effectively. If beating the game were only as simple as choosing to cooperate, any choice after stating an intention to work together would be meaningless. As stated above, the conflict comes from the board itself. More specifically, the conflict comes from dealing with the consequences of the “Progression of Evil” phase. Every action taken there threatens the players with the approach of a loss condition. Choosing to place a siege engine on the board brings the game closer to having a fatal number of siege engines, and it takes serious player effort to remove one. Choosing to draw a black card will most often cause one of the several quests on the table to slip closer to a loss condition, which would put black swords on the Round Table. Two specific quests even cause more siege engines to be placed on the board. Lastly, a player may choose to sacrifice a point of life.

In many games, choosing to sacrifice a point of life would be questionable, even unthinkable. After all, if you lose all your life points, you are eliminated from the game. However, a number of factors make this the most reasonable course of action. With the exception of a single specific black card, you choose to enter situations when you may lose a point of life. It is unlikely that you would take damage from a completely unexpected source, so there is little reason to build up a buffer of life points. The alternatives are also worse in most cases. A black card or a siege engine hurts everyone, not just the player.

This brings us to a theme of the game that did not become apparent to me when reading the manual, and only became apparent during actual play, as is common in game systems design, and helps me to illustrate a set of three important terms in the discipline of game rules systems design. A mechanic is a rule within the game. The ability to choose to sacrifice a point of life is a mechanic. This creates a dynamic, a player behavior that tends to manifest in a reaction when players interact with the mechanic. In this case, the dynamic would be a player looking at the three options, evaluating them in the context of the current playing field, and making the decision to sacrifice that point of life, believing that to be the option that will stall defeat. This gives rise to an aesthetic, a player emotional response to the game. In this case, the dynamic of choosing to sacrifice of the self for the betterment of the whole gives rise to an understanding that this is a game where defeat is likely, and personal sacrifices must be made if there is to be any hope of victory, creating a feeling of tension and willingness to work with the group. The mechanics of the game as a whole interact with the players, who adopt certain dynamics in reaction as they try to discover a way to win, and these behaviors and perceived expectations create emotional responses in the players.

Playing Shadows Over Camelot contributed significantly to my ongoing research into cooperative gaming. A number of dynamics were discovered that simply reading the mechanics of the game without putting them into play could not have revealed. A single shared goal is vital to the success of players. While they can be given different abilities that might help them reach that goal, victory must be done as a group. A player’s avatar might die, eliminating the player from the game, but as far as the game is concerned, the player will still win if the rest of the group wins, and in some cases, a player might even elect to lose their last life point and be removed from the board if it will make a difference between winning and losing. A number of cards, both negative and positive, present the players with the option to take a penalty or reward completely for themselves, or to distribute it among the group, and prioritizing this is an important part of gameplay. Another important element seen here is that for every player, one “bad thing” happens. This creates a threat that scales itself in proportion to the number of players in the game. Though I have not experimented with different numbers of players, in theory, this would allow for the same level of challenge in the game whether you have three players or seven.

I hope to next examine the Lord of the Rings board game, which is also focused on cooperation, though this has no possible “traitor”. Arkham Horror is another game I hope to take a look at, but because it has similarities to Shadows Over Camelot, I feel it would be better to look at a game with similar themes that approaches it in a very different way.